Description of Empirical Work, including survey forms and experimental instructions

Contents:

1. Interviews with Traditional Healers:

2. Health Seeking Behavior and Health Facility Evaluation in Tanzania (Project Description)

3. Retrospective Consulation Review

4. Health Facility Quality Evaluation (Liberia)

Interviews with Healers in Tanzania Cameroun and Ethiopia.

As part of my study I interviewed traditional healers in Cameroun, Tanzania and Ethiopia. If you would like to read the notes of these interviews you should download this pdf file (tradheal_inter.pdf). The identities of the interviewee's cannot be released, but you probably don't need this information. The surveys are open-ended, so not all of the same questions were posed to all healers. I took notes during the interviews and wrote up my notes on the same day as the interview was completed.

Health Seeking Behavior and Health Facility Evaluation in Tanzania (Project Description)

Description of Country Project

This study examines all of the health facilities available to rural residents in parts of Monduli and Arumeru rural districts of Arusha region in Tanzania. Since these households can seek care at a wide variety of locations, the study includes all public and NGO facilities in the rural and urban areas accessible to these households as well as all of the private facilities that these households are likely to visit. The study seeks to characterize the variety of facilities, and the quality of these facilities that are likely to be important to rural households.

The study focuses on outpatient care and the services likely to be important to outpatients at these facilities, including a variety of process quality and structural quality measures. Process quality includes consultation quality, prescription practices, nursing services (wound dressing, injections and administering medications) and the use of laboratory services. Structural qualities include inventories of most equipment necessary for outpatient services as well as drug stocks and the condition of the building and surroundings. Data on the characteristics of the doctors at each facility, including tenure, experience and training as well as regular fees were also collected.

An important element of the study included explicit examination of the differences between capacity and practice.

Findings:

- The performance of clinicians on a test of ability (the vignette) compared to their activities in consultation with their regular patients shows that most clinicians regularly perform at levels significantly below their abilities. (Leonard and Masatu, 2005)

- Even examining the level of performance with regular patients, clinicians demonstrate important differences between their ability and practice. The data show that many clinicians exhibit a classic Hawthorne effect in which they increase the quality of their care immediately that the team arrives. However, even within the context of our evaluation (usually about 2 hours) the quality falls markedly, by about 10%. This suggests that clinicians are capable of higher quality care than they usually deliver (Leonard and Masatu, 2005)

Survey Instruments

Health Seeking Household Interview

Modules for Health Facility Evaluation:

- Absenteeism Survey

- Vignettes

- Vignette Reader (instructions), pages 1-12 of vignettes.pdf

- Vignette Instruments (8 vignettes) pages 13-20 of vignettes.pdf

- Direct Clinician Observation

- Consultation cover sheet, page 1 of opdeval.pdf

- DCO instrument, pages 2-5 of opdeval.pdf

- Nursing Evaluation:

- Drug Dispensing, page 6 of opdeval.pdf

- Wound dressing, page 7 of opdeval.pdf

- Injections, page 7 of opdeval.pdf

- Infrastructure Evaluation: Facility and Equipment, page 8 of opdeval.pdf

- Infrastructure Evaluation: Drug Availability, page 9 of opdeval.pdf

- Patient Exit Interview (Swahili and English), page 10-11 of opdeval.pdf

- Retrospective Consultation Review (Swahili) , page 12-15 of opdeval.pdf. [See printing instructions for DCO instrument, below]

Manuals:

- Vignettes, Vignette Reader (instructions), pages 1-12 of vignettes.pdf

Notes on the Survey

Permission to observe consultations and process for protecting patient health

Each patient was approached by a member of our team and asked if they wanted to participate in the study. If they agreed, they were given a card with a unique observation number on one side (patient id), and the written consent explanation on the back (it had been read to them already). At every stage in their care, we would refer to this number. The patient was asked to hand their card to the researcher when they entered the room and they would collect it on their way out. If a patient did not have a card, it was assumed they had not given consent and the clinician would step out of the room for their consultation. As part of the conditions to perform this study, we agreed that any patient who received potentially dangerous diagnoses, treatments or health education would have their card marked by the clinician. When the exit interview was filled, if the researcher filling the exit interview saw a mark she was to instruct the patient to wait at the facility so that she could receive further care. Then at the end of our study, this patient was brought back to the consultation room and reexamined by both our researcher and the original doctor.

Vignette Design

The consultation quality surveys (Vignettes and direct clinician observation) were designed to cover patients suffering from conditions that are prevalent in Tanzania. Its use is therefore tied to the fact that clinicians can and do see patients like these frequently. In a setting in which malaria and upper respiratory tract infections are common, this survey might be useful. But it should always be designed to fit the national standards.

For the vignettes, many clinicians ordered lab tests, the results of which were not provided in the survey (except for the TB vignette). We chose only conditions that could be diagnosed with lab tests. Of course, a clinician with access to a lab will want to use that to confirm his diagnosis. To balance the abilities of clinicians with lab access and those without lab access we required the clinician to give a preliminary diagnosis,” awaiting the hypothetical lab results. History taking and physical examination in these cases should provide plenty of evidence for a preliminary diagnosis.

DCO design

For the DCO instrument, it was important that all possible history taking and physical examination items be on the same side of a sheet of paper. Thus we produced the forms in the following manner. There are four pages to this instrument and they are designed to be printed as a booklet (1 sheet of paper folded in half) with page 1 on the front, page 2 and 3 facing each other in the middle, and page 4 in the back. In this manner pages 2 and 3 are both available at the same time. Since the order of a consultation cannot be easily determined, (clinicians may alternate between history taking and physical examination), we wanted to avoid the researcher shifting back and forth between pages, or flipping a page back and forth, since this is distracting. The goal is for the researcher to blend into the background as quickly as possible.

The DCO instrument was designed to follow patients who suffered from primary symptoms fever, cough, diarrhea and symptoms of STDs. When patients suffered from more than one primary symptom, we coded all the applicable items. The STD category provided useless information, largely because a poor quality consultation will not notice that the condition is an STD. If a woman came in with an upset stomach, it is possible that she was suffering from PID, but it would seem rash to code all such cases as “indicative of STDs.” This set of items should be dropped or reworked.

The Exit Survey

The exit survey should have asked about socio-demographic characteristics of the patient (such as education and occupation). These would have taken little additional time and added significantly to our analysis of patients. We could not ask questions on income, etc, partially due to sensitivity and partially due to time limitations.

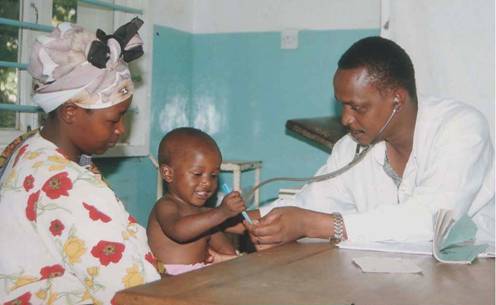

Figure 1 Dr. Kyande, lead clinician enumerator, at his regular practice

Short discussion of the vignette methodology used to measure quality of care.

Retrospective Consultation Review

The English Version of the retrospective consultation review instrument (the actual survey was in Swahili) intended to be administered as soon after the end of the consultation as possible: RCR Instrument

Health Facility Quality Evaluation (Liberia)

Write up of protocol for evaluation Implementation Science 10 (9)

All the instruments, write up and training tools are available at the project website Health Facility Quality Assessement (Liberia)