My second excursion, in the spring semester of my freshman year, was a trip across the Bay to a pair of locations in Cambridge. It wasn’t the most popular choice — only eleven of us had signed up in the first place, and four of them ended up bowing out at the last minute — but I was excited. I had been swamped for weeks, and even Easter the next day looked like it would be more working than relaxing. Having a day to take off from campus, see the restoration efforts being conducted on the Bay, and take a gander (haha) at some waterfowl seemed like exactly what I was looking for.

When we arrived, I wasn’t immediately impressed. Horn Point Lab was in the middle of moving to a larger building, and the first place we stopped was in a state of disarray, stacked with boxes and a spread of devices that had long outlived their initial purposes. Here, surrounded by the evidence of the lab’s long-standing research, we learned about a few of the projects that HPL was engaged in.

One project at the Horn Point Laboratory is focused on discovering the current and future impacts of climate change on bays like the Chesapeake. Estuaries in particular are vulnerable to sea level rise and rising temperatures, since the ecology in different regions is highly specific and relies on a number of factors. Changes in temperature leave species with nowhere to go, since certain species can only thrive in specific salinity levels that will not change at the same rates as temperature. These situations are both measured directly, with a variety of autonomous monitoring tools in place, as well as being modelled based on historical trends in species movement as a result of these changes. Horn Point Lab participates in this nationwide effort through the collection of salinity, temperature, and depth data across the Chesapeake Bay, combined with the monitoring of species in the Bay.

Another project Horn Point has been involved in, our tour guide pointed out to us as we passed through the halls of the visitor center, is the monitoring of Cove Point Marsh. Cove Point is a Maryland Natural Heritage Area, home to many rare or endangered plant species. Following a severe storm, salt water from the Bay flooded the marsh and damaged its ecology. Since then, the area has been rebuilt using dredged materials, and the marsh has been restored. Horn Point Laboratory keeps track of the area to ensure the success of the project, monitoring its salinity, the width of the beach, the wetland coverage, the structure of vegetation, and the presence of invasive species. Together, these factors allow Horn Point scientists to keep track of the potential threats to Cove Point going forward, and respond to any potential threats to the area.

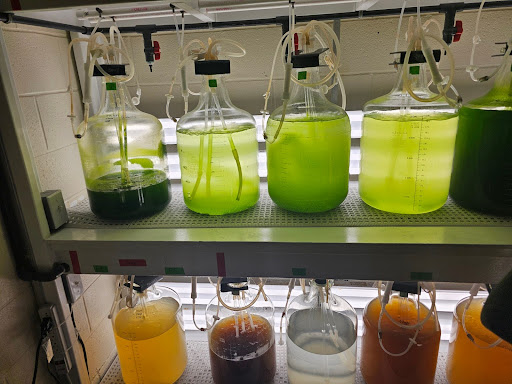

Eventually, we ended up at a far more impressive building. Filled with spawning chambers, massive growth tanks, and an algae-growing room that looked honestly delicious, the building was home to one of the largest projects at Horn Point Lab, their oyster hatchery. Oysters are an important element of the ecology of water systems, serving as filters for the water as well as creating habitats for other species with their shells. However, over time, the oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay (as well as in many other locations) has decreased significantly, particularly in the aftermath of Hurricane Agnes. This issue leads both to changes in the ecosystem, due to increases in algae and decreased filtration, as well as economic impacts on the surrounding areas, which have a heavy investment in the seafood industry. Because of this, monitoring and managing the oyster populations is an important task for the continued health of both the Bay and of the people living around it. Oyster populations are tracked in the Bay through an annual oyster survey, where biologists collect samples from across the Bay. These samples are used to measure their reproductive success, the spread of disease, and several other factors. Recent samples, indicating an increasing population in the Bay, are in direct alignment with the efforts of Horn Point Lab, which has released over a billion oysters into the Bay in the past 10 years.

Horn Point doesn’t just focus on research, though. As a publically funded institution, it also works to reach out to the residents of the area. To this purpose, the Lab hosts a number of options for interaction with the public. Every October, Horn Point hosts an open house, where anyone can come to learn about the research being conducted, see the oyster hatchery in person, and participate in hands-on exhibits. HPL also hosts virtual seminars, highlighting the work they do to manage the health of the Bay.

After we left the lab — and after grabbing a quick bite at a nearby Taco Bell — we headed on down to the second half of our trip. Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, located just ten miles south of Horn Point, works to promote the same biodiversity as HPL, but in a very different way. Established in 1933, the refuge serves as a sanctuary for migratory species of waterfowl and other birds. Blackwater’s tens of thousands of acres span hardwood forests, tidal marshes, and even cropland that can serve as a home for a diverse range of species. While there, we saw a wide array of less common birds — including egrets, ospreys, herons, and bald eagles — in addition to a number of ducks, turtles, and other small wildlife.

In addition to serving as a rest stop for migration, the refuge also serves as a point of outreach for the public. It features 20,000 acres open to the public, with five miles of hiking trails as well as trails for paddling and cycling. During our trip, we took the Wildlife Drive, which gives visitors a view of a wide range of wildlife as well as providing them with information about their surroundings, and how the refuge is changing over time. Among these changes were the presence of Phragmites, an invasive species of reed that spreads rapidly in disturbed areas. Because it spreads so quickly, Phragmites grows well in areas where forests have been pushed back by rising sea levels and their associated salinity. We also saw evidence of the sea level rise in the presence of “ghost forests”, large bands of dead trees that were drowned out by the increasing reach of the tides.