A Seminar with Dr. Rajesh Maingi

Zoom Seminar: Tuesday, November 25th, 7p.m.

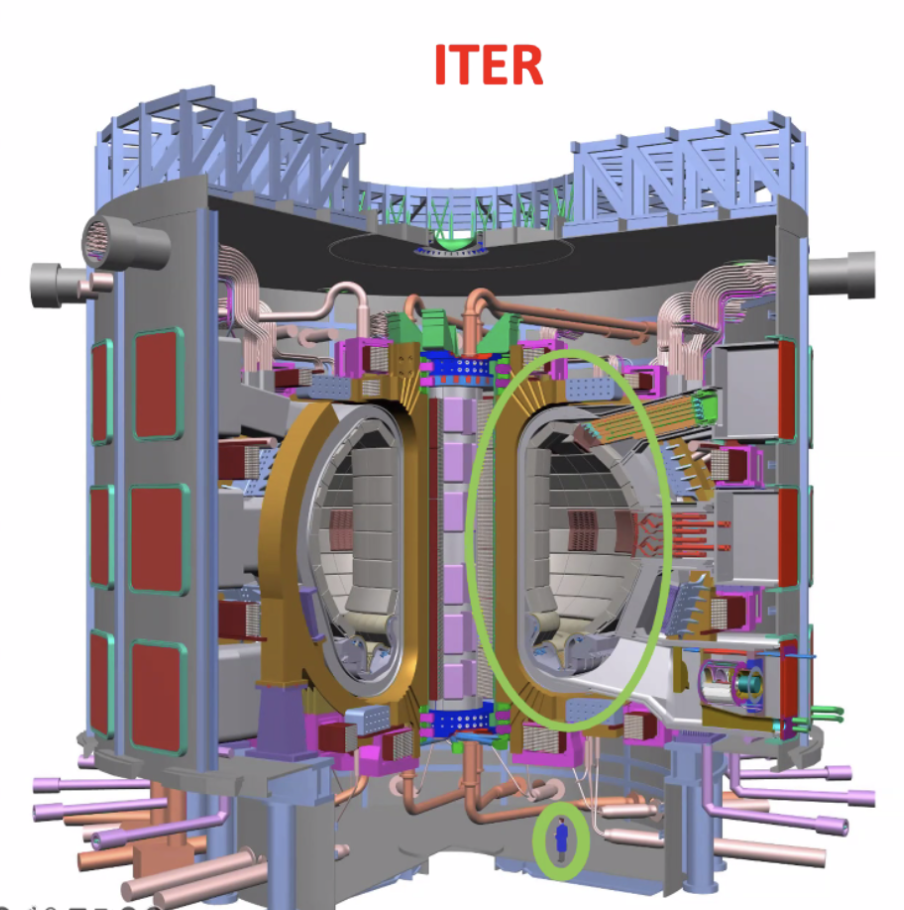

New ITER Tokamak Model

Introducing the Concept: Fusion Fusion is the process by which two small atomic nuclei merge to create one larger nucleus. In this process, the resulting compound retains slightly less mass than the two preceding atoms, generating massive amounts of energy through Einstein’s E=mc^2 relationship. There are a couple of ways we have found fusion propagates. Two common models are the proton-proton and deuterium-tritium (D-T) fusion chains. Proton-proton fusion involves two hydrogen nuclei generating helium-4, and it occurs in our sun at relatively low temperatures (10-15 million K) and intense pressures. D-T chains involve heavy hydrogen isotopes, H2 and H3 to generate helium-4, with an additional fast neutron that travels at 17% light speed and carries 160 billion K worth of energy. These chains occur at higher temperatures (100 million K).

Initiating fusion State: Despite how impossible these numbers sound, we see fusion taking place every day, looking at the glowing sun in our sky. In stars, immense, overpowering gravitational forces have the power to compress atoms enough to force fusion. It takes A LOT of force to overcome electromagnetic repulsion at that scale, so one of the most fundamental challenges of fusion was discovering how to recreate ‘fusion-able’ conditions on Earth. Our solution to this obstacle is to heat our elements to the point where they carry enough kinetic energy to collide and overcome the repulsion with their instantaneous impact force.

How do we heat material to such an extent? There is a combination of three main methods that are applied to initiate the fusion state. Resistive heating consists of a powerful transformer that pulses strong currents through the ionized gas. The gas carries resistance (like a wire), as gas molecules interact, they generate thermal energy, which results in a heating effect. This method is effective up to 20 million K. Wave heating shoots electromagnetic waves (radio waves work best) into the plasma, and bond resonance in the ionized particles picks up the e-mag energy. This method is effective up to 200 million K. Lastly, neutral beam injection (NBI) involves shooting very high energy particles (like hydrogen or deuterium) into the plasma to transfer lots of energy through high velocity collisions. This method requires that neutral particles be used, as the ionized plasma (or magnetic confinement field) would redirect any charged particles from reaching the sample. NBI work up to 300 million K. So, in a real tokamak device, resistive heating is used to reach moderate temperatures, then wave heating and NBI work to reach 100+ million degrees.

When handling substances reaching millions of Kelvin, we have to ensure our materials are not destroyed by the immense temperatures (materials tend to fail ~1000K). We have found two main ways to handle all of this heat and energy to initiate fusion on Earth: inertial and magnetic confinement. In inertial confinement, small pellets of the gas are rapidly compressed and heated by strong energy beams, so the gas reaches a brief state of fusion. Magnetic confinement, which Maingi works on, generates strong fields (100x mag. Field at Earth’s surface) to keep the critical ionized gas from hammering away at the reactor walls. Magnetic containment shows promise for establishing steady-state fusion processes, with the idea that these fields would be able to contain the plasma continuously over extended periods of time.

Today, fusion exists in a pivotal position. Modern research has led us to effective heating methods, sufficient plasma generation, and an energy output that is promising for a future of practical power production from fusion reactions. Nuclear fusion is the most energy dense method of energy release (around 340 trillion Joules/kg fuel), millions of times more powerful than fossil fuels. So, mastering ways to properly harness this energy would be a key development in a green, limitless future. As promising as the technology is, there are still significant challenges before we can see truly effective fusion reactors. Stabilizing plasma for longer durations is necessary fusion for prolonged, steady energy output. Also, improving production of fusion fuel (like deuterium and tritium) is needed for upscaling the industry. Besides critical scientific developments, we must also overcome large upfront costs to see fusion implemented into the energy grid.