| Table of contents | Previous page in book | Next page in book |

MINING DINOSAURS

Nonetheless, the pit mines around Muirkirk, Prince George's County, Maryland, continued to be worked. One of the reasons was that the high manganese content of its ore gave it a great tensile strength, allowing it to withstand forces as high as 52,160 pounds in the pig (Singewald, 1911). This special property had been appreciated since colonial times but was only understood recently through modern metallurgical chemistry.

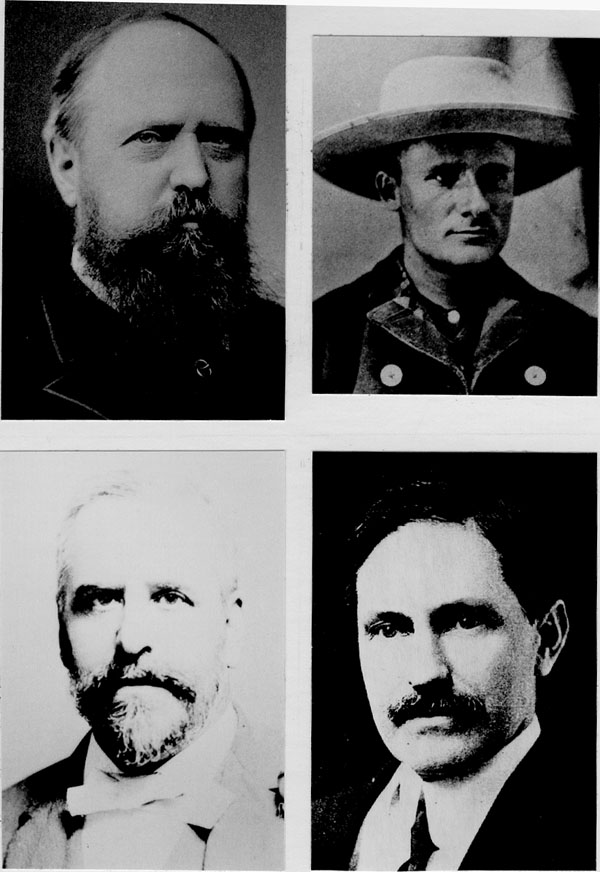

On 13 May 1887 John Wesley Powell, Director, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), wrote Professor O. C. Marsh (Fig. 7a) of Yale University, asking him to send several professional collectors to study the dinosaurs of the Potomac Group with the intent of learning more about them and determining the age of the formation. Powell wrote:

| As I think you are aware, the Potomac formation of this vicinity (the Upper-Mesozoic, or Wealden, of Rogers and others) has yielded a wonderfully rich flora, of exceptional interest in that it represents the transition from prevalently polycotyledonous to prevalently dicotyledonous forms. Very few animal remains have yet been found in the formation, but these are mainly vertebrate. Professor Fontaine, of the University of Virginia, is at work upon the flora of the formation; Mr. McGee is at work upon its structure and general characters; but no part of it has been carefully examined by competent collectors for animal remains. Now can you not arrange to send one or two experienced collectors to Washington during the coming summer or fall to carefully examine the formation in the localities that have already yielded vertebrate remains in small numbers? You will thereby, doubtless, greatly enrich the Potomac fauna, and probably determine the age of an interesting formation; for despite its luxuriance, the flora does not decisively indicate whether the formation is Neocomien or Jurassic. (Marsh Papers) |

| Five months later, on 4 October 1887, Marsh's famed and dogged collector, John Bell Hatcher (Fig. 7b), arrived at Washington, D.C. to undertake the task. He completed his stay four months later, 29 January 1888 (Appendix C). A year later, on 18 January 1889, he stopped briefly in Washington to pick up some additional fossils (Hatcher Diary, 1887, 1888). In a letter dated 23 October 1887 to Professor Marsh, Hatcher wrote: |

| Fossils are very abundant here, but mostly small. The past week I have taken out about 200 teeth, one piece of skull. . . [and] two vertebrae. Have I think found remains belonging to fishes, reptiles and mammals as well as bivalve and univalve mollusks all of which are probably new. . . . . In collecting what I have I don't think I have moved over a bushel basket-full of dirt. Now what do you want me to do here? The weather will probably permit of my working here to advantage for six weeks to come and the locality has every appearance of being inexhaustible. (Marsh Papers) |

| During the early part of the sojourn, little of significance was accomplished, as his guide, Frank McGee of the USGS, was confusing younger formations like the Aquia with the Potomac. By December, 1887, Hatcher was on track and working in the real Potomac Group beds between Baltimore and Washington. Digging the bones from the clay was difficult, and the bad weather made the situation more frustrating (Hatcher Diary, 1887, 1888). The exasperated Hatcher wrote Marsh several times suggesting that without help it was best to give up the effort. On 16 December, Hatcher responded to a letter from Marsh and informed him of a proposal made by Charles E. Coffin (Fig. 7c), owner of the Muirkirk Iron Works and the mine called Swampoodle (Fig. 9), from which most of the bones were coming. Coffin had abandoned work at Swampoodle sometime earlier, and it had begun to fill with water. He suggested that he and the USGS share the cost of reopening the pit. Coffin would get the ore and the USGS would get the bones. |

| I received yours of the 15th this evening. I write to put before you a proposition made by Mr. C. E. Coffin who owns the old iron ore bank where I am digging bones. He quit working it some two years ago because it was no longer profitable. He now says that he will lay the track and put his engine and cars and 7 men to work in it again for two months and mine for ore and bones too if we will pay one half the expense, which one half is not to exceed five dollars per day, but we must continue for at least two months. If you want a good collection from here this seems to be the better way of getting one. I can get a few working the way I have been, but not many. Please answer by telegram.

I would be glad to see you before I leave Washington and have you visit the localities here with me. I found a tooth today different from anything I have yet found and a vertebra that appears also to be different. I do not know that you will care for my opinion about accepting Mr. Coffin's proposition, but I think that if you want a good, complete collection is would by all odds be best to accept. But if you only want a few more to determine the exact age of the formation, I doubt whether it would be advisable to enter into a contract requiring the expenditure of so much time and money. (Marsh Papers) |

An even split of the expenses was agreed, and several men began pumping out and working the pit in December, 1887 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.— Receipt from Charles Coffin in 1887 on company stationery for work done digging for dinosaurs by J. B. Hatcher (Marsh Papers). All Hatcher's digging and collecting enabled Marsh to report finding "new genera of Dinosaurs from the Potomac formation" (letter from W. J. McGee to O. C. Marsh, 4 January, 1888 in the Marsh Papers). Professor Marsh joined Hatcher on Sunday, 8 January 1888, and returned to New Haven, Connecticut on Saturday, 21 January 1888. While there, the two of them and their assistants recovered hundreds of bones and other fossils. One week later, after Marsh had returned to New Haven, Hatcher sent him another box of fossils, including one Hatcher thought looked "much like an Allosaurus tooth, but it is much larger and stronger than the one I sent you last . . ." (letter from J. B. Hatcher to O. C. Marsh, 28 January, 1888 in Marsh Papers). Today, these fossils form the basis of the main collection of Potomac Group dinosaurs (Early Cretaceous age) housed at the National Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. These events were chronicled in Hatcher's diary (Appendix C). From the bones they found, Marsh named several new species of dinosaurs, including Priconodon crassus, which is an armored dinosaur, large meat-eating dinosaurs and a number of sauropods. Shortly after the work of Marsh and Hatcher, what is effectively the rest of the Smithsonian's collection was made in the early 1890's by Arthur Barneveld Bibbins (Fig. 7d), a Johns Hopkins University graduate student and local geologist. Concerning special plant deposits at Muirkirk and Contee, Bibbins wrote: |

| The iron ore of the Muirkirk region occurs to a considerable extent in an exceedingly tough blue clay impervious to water, and highly charged with lignite ("blue charcoal clay" of the miners). These beds are noteworthy on account of the abundance and excellent preservation of these lignitized vegetable stems and trunks, many of which will probably be found determinable. All of them lie horizontally and are much compressed. The stems also penetrate the masses of carbonate ore, which have evidently been formed about them as nuclei, and it is said that their abundance in the ore materially facilitates its reduction. These nodules of white ore are reported to contain occasional fern impressions, but none of these have yet come under the observation of the writer.

Among the more interesting fossils from the blue charcoal clay are the sequoian cones converted to siderite. According to Professor Ward the specimens hitherto obtained have mostly been secured from the so-called "old engine bank," where they are probably most abundant. They have lately been found at a number of other points in the region of Muirkirk and Contee. From the same beds casts of cones have also recently been obtained differing in species from those usually occurring. A perfect seed was also found and other determinable vegetable structures which will be described in a later paper. Overlying the bed of "blue charcoal clay" there is frequently found a bed of "brown charcoal clay," which presents the appearance of having been produced from the former by weathering, though inclined to be less compact, considerably arenaceous and therefore pervious to water. The lignitized stems of these beds are much less perfectly preserved, and no cones have been seen in the same. The brown color of the clay has apparently been derived from the limonite produced by the weathering of the original masses of siderite. The vertebrate remains are considerably more abundant here than in the lower beds of "blue charcoal clay," though they too, are less perfectly preserved. Above these beds of lignitic clay, and commonly forming the uppermost member, is usually found a bed of highly arenaceous clay destitute of lignite and containing a considerable number of quartz and other pebbles. On the surface of this member, in close proximity to the lignitic clays above described, a cycadean trunk was recently found. This bed also contains fragments of silicified coniferous logs (the "petrified chips" of the miners), and one large highly silicified saurian bone was recently taken from the same member, near its contact with the lignitic clays below. It should be remarked that the Latchford mine near Contee, from which Mr. Tyson obtained one of the original cycadean trunks is about one mile north of the point where the trunk just mentioned was found. About the same stratigraphic relations exist there, and Tyson's cycad probably weathered out of this pebbly loam, (which here also contains much silicified wood), and rolled down upon the exposed surface of the iron-bearing clay, which until now has been regarded its original source. (Bibbins, 1895) |

| Bibbins, also made a special and successful effort to collect cycadeoid remains. Ward (1894) shared his insightful observations concerning Bibbins' collecting methods: |

| In appointing Mr. Bibbins curator of the college the right step has been taken to further these ends. A post-graduate of Johns Hopkins at the time of his appointment, Mr. Bibbins has been trained to the best scientific work. He is naturally endowed in a high degree with true scientific instincts as well as with practical judgment and good sense. It is these qualities which have led him to adopt an entirely new method in searching for scientific material. Knowing the rarity of fossil cycadean trunks and their great value to science, he set himself the task of trying to secure some of these for the college museum. But, instead of undertaking a hopeless and aimless quest, as has been done by geologists and collectors in the past, he chose to avail himself of the knowledge of the inhabitants of the districts in which the cycads were believed to occur. Supported by the Woman's College, which furnished him the means of transportation and met the small expense of his work, including an occasional pour boire to some needy farmer or miner who possessed information of great value, and usually gave it freely, he proceeded to visit the houses of the native population, and placing himself on a level with their powers of understanding, he was able to interrogate a large number of persons in such a way that they could not fail to comprehend his meaning. Having secured one specimen, he carried it about in his wagon and showed it to all whom he met. His surprise was great to find that a large proportion of the inhabitants of the iron ore districts had at some time in their lives seen similar things and were able to recognize them. In some cases a person to whom he would show his specimen would reply at once that there was such a stone in his barnyard or near his house, and by a very little negotiation he was able easily to secure it. By far the greater number, in fact nearly all, of the specimens were thus found in the possession of the people. Many of them could remember having ploughed them out of their fields, or taken them from their ore pits; others there were that had lain so long around farm houses whose occupants had several times changed that it was impossible to trace them to their original source, but usually even in such cases there was a tradition lingering in the family with regard to the peculiar stones. The reason why they were so universally picked up and brought to the house or the workshop or the barnyard or laid up in some conspicuous place seems to be that their peculiarity was instantly recognized. A countryman knows every stone that he has seen about his place, and if there be one which differs markedly from all others, especially if it has a certain symmetry of form or shows unusual and regular markings, he at once distinguishes it, is impressed by its appearance, and probably, at first at least, couples with the notion of its strangeness some vague idea of its possible utility or money value. He therefore invariably picks it up and sequestrates it in some way. After many years, finding that there is no demand for it, that no one knows any use to which it can be put he eventually loses interest in it, and it is pushed aside, forgotten, and perhaps covered up in some obscure corner. So that in addition to the specimens that Mr. Bibbins actually obtained, there remain quite a number which are known to exist, but which for the present cannot be found. Mr. Bibbins always frames his questions with skill, taking care not to ask leading ones, realizing that the desire to please is liable to color the answer and make it conform to what it is supposed he desires to have said. He therefore always takes pains to induce these people to tell what they know independently of any suggestion on his part. As an illustration of the accuracy with which such persons often observe and remember facts, may be mentioned a case in which one of these traditional lost specimens was being inquired after from an octogenarian who remembered seeing it some forty years before, and when asked if the "holes" in the stone were "round" he replied "No, they were sort o' three-cornered," a remark which rendered it certain that the object was really a cycad |