| Articles by subject: Topics: Latin American

economies | ||||

| |||||||||||||

| |

| |

|

|

LAST October, a popular uprising led by radical leftist groups ousted Bolivia's president, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, at a cost of 59 dead. The vice-president, Carlos Mesa, took over the top job, and is trying to steer a disgruntled country riven by ethnic tension until the next election in 2007. On July 18th, he faces a crucial test. In a referendum, Bolivians will be asked what they want to do with their oil and gas wealth—the issue that served as a catalyst for protest last October.

Bolivia is the poorest country in South America. But thanks to foreign investment in exploration, it now has the continent's second-largest gas reserves outside Venezuela. Bolivia also has a habit of setting political trends. So the referendum may be seen as a sign as to whether—or at least on what terms—energy multinationals have a future in South America.

|

| |

| |

|

|

The radicals who led last October's protests want to renationalise the oil and gas industry, largely privatised by Mr Sánchez de Lozada in an earlier term in the mid-1990s. Mr Mesa is trying both to appease social protest and salvage the possibility of future private investment in energy. It is a difficult balancing act. One sign of that is the referendum's convoluted questions (see table). These seem judiciously crafted to ensure approval.

The first three questions represent a partial retreat from the free-market policies espoused by Bolivia since the mid-1980s. These delivered steady economic growth—but not enough to dent poverty. Contrary to appearances, the last two questions are an attempt to gain popular backing for gas exports. These are crucial to Bolivia's economic prospects. But the issue has become entangled with another one: the country's continuing hurt at the loss of its coastline to Chile in an 1879-83 war. That killed a scheme backed by Mr Sánchez de Lozada (known to Bolivians as “Goni”) to export gas to California via Chile.

Bolivians have almost no previous experience of referendums. Officials hope that they have turned the vote into one on whether to back or sack their president. Mr Mesa, a historian of little political experience, is popular, but lacks a dependable majority in Congress; he has shunned most of Bolivia's discredited political parties. “If there is a No vote Carlos Mesa will go. If he gets a Yes he will gain an enormous level of legitimacy,” says Ramiro Molina, a historian at La Paz's University of the Cordillera.

Opponents on the right have denounced the referendum questions as “tricks”. Naming Goni, who is now deeply unpopular, in the first question ensures its approval. The radicals wanted a question on renationalising the industry—something Mr Mesa has ruled out. Evo Morales, the leader of the coca workers and the runner-up in the 2002 election, has given equivocal support to the government, but wants a No vote on the last two questions.

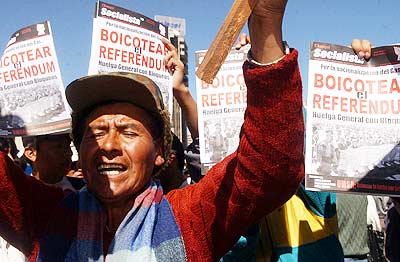

The leftists first called for voters to write “nationalisation” across the ballot. They have since threatened to disrupt the vote by blocking roads and burning ballot boxes. Though disorder is possible, the signs are that Mr Mesa will get his referendum victory. Only a simple majority of votes cast is required for approval, so boycotts would not help opponents.

So far, Mr Mesa has been a fireman, though a fairly effective one. Street protests have continued, but with declining force. If the referendum gives him a new mandate, he will have a chance to settle the energy issue. Initially, he wanted to approve a new hydrocarbons law before the referendum. Now a new law is to follow the popular vote. It is certain to include an increase in taxes on multinationals with fields in Bolivia, who include Spain's Repsol-YPF, Brazil's Petrobras and Britain's BP and BG Group. The industry has invested some $3.5 billion since 1997. Oil and gas producers say that the government already takes 69% of their pre-tax profits; in 2003 these totalled $122m on revenues of $806m. The government also wants to increase its say over the destination and price of exports of oil and gas. And it wants to revive the state oil company, giving it a stake in all future projects.

When the existing hydrocarbons law was approved in 1996, “the priority was finding reserves,” says Carlos Alberto López, a former energy minister and now a lobbyist for the industry. “Now, its opening markets.” He claims that the multinationals accept that the law needs revising. But they are opposed to unilateral changes in contracts for existing fields. “The government has allowed the misconception to grow that a yes vote will mean an automatic change to our contracts and this is not the case,” says Mr López.

If the referendum is defeated and Mr Mesa falls, renationalisation of the industry might follow. Approval would be a less bad outcome. But already, uncertainty has caused foreign investment in Bolivia to plunge. Next door in Argentina, President Néstor Kirchner says he will set up a new state oil company. In Venezuela, Hugo Chávez relies on multinationals to produce a rising share of his country's oil. But with Mr Kirchner, he is setting up Petrosur, a regional state-owned enterprise aimed at strengthening government control over oil. It is hardly surprising that, Brazil and Trinidad apart, the continent barely figured in a worldwide survey of new oil developments published this week by Reuters. Oil and gas may be a problem, but having none is a bigger one.

| Copyright © 2004 The Economist Newspaper and The

Economist Group. All rights reserved. |