Hear Cisneros read from Caramelo

(6 minute audio)

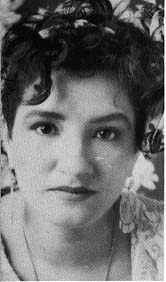

Representative Text: Sandra Cisneros's Caramelo (2002)

"I'm trying to write the stories that haven't been

written. I feel like a cartographer; I'm determined to fill a literary void,"

Cisneros says . . . . Born in Chicago in 1954, Cisneros grew up in a family

of six brothers and a father, or "seven fathers," as she puts it. She recalls

spending much of her early childhood moving from place to place. Because

her paternal grandmother was so attached to her favorite son, the Cisneros

family returned to Mexico City "like the tides." "The moving back and

forth, the new schools, were very upsetting to me as a child. They caused

me to be very introverted and shy. I do not remember making friends easily,

and I was terribly self-conscious . . . . I retreated inside myself." It

was that "retreat" that transformed Cisneros into an observer, a role she

feels she still plays today.

--from

"Sandra Cisneros: Conveying the riches of the Latin American culture"

read first

read second

Interview From the September/October 2002 issue of Book magazine

Then Read the Novel

Caramelo has 86 short chapters and a Fin

Read through Chapter 50 to page 299 for Tuesday

Please Submit Topics and Questions You Would Like to Discuss In Class

Finish the novel for Thursday

Please Submit Topics and Questions You Would Like to Discuss In Class

Interview From the September/October 2002 issue of Book magazine

Then Read the Novel

Caramelo has 86 short chapters and a Fin

Read through Chapter 50 to page 299 for Tuesday

Please Submit Topics and Questions You Would Like to Discuss In Class

Finish the novel for Thursday

Please Submit Topics and Questions You Would Like to Discuss In Class